From Portugal, with Love

It's the making of the food, not the food itself that's our Christmas tradition.

BY MID-DECEMBER, my social feeds are full of Portuguese people recreating their grandmother’s exact Christmas Eve menu from the Old Country—same codfish, same sweets, same everything, down to the brand of paper napkins. That… was definitely not my childhood.

I grew up as first-and-a-half-generation Portuguese: my father right off the boat from Maia, São Miguel (above), my mother American, and me planted somewhere between the Azores and the mall. There wasn’t a laminated list of What We Eat on Which Holy Day taped to the fridge. We didn’t have the whole “on the 23rd we soak the salt cod, on the 24th we eat it, on the 25th we roast this, on the 26th we fry that” thing nailed down.

Our holidays were a little more freestyle, a little more Fall River than Fátima.

But what we did have was the making of the food.

Some of my most vivid Christmas memories aren’t of sitting at the table—they’re of standing in overheated kitchens watching the women in my father’s family go to work. My Leite aunts and my Vo Leite would haul out enormous metal wash tubs—actual wash tubs, like the kind you could bathe a toddler in—and that was their mixing bowls for dough. They’d plunge their arms in up to the elbows, working this silky, elastic dough meant to feed what felt like the entire Portuguese population of Massachusetts. On every flat surface in the apartments were bowls and pans of something soaking, drying, or proofing. I remember it as “salt cod on every surface,” a kind of nativity scene in which the baby Jesus smelled faintly of the Atlantic.

Because so much of what we ate was homemade, there was this constant round-robin of ingredients passing through the family. My father would make his wine and his brick-red massa de pimentão—the garlicky pepper paste of the gods. My aunts, his sisters, would use that wine and paste to marinate pork for chouriço sausage. Then THAT chouriço, stained with my father’s peppers and scented with his wine, would find its way into our soups, stews, and roasts. It was like eating a family tree: roots, branches, and all.

And in the background of all this was another story, from the Old Country, that always catches in my throat when I tell it. Back on the island of São Miguel, where my family’s from, there was a different kind of holiday “tradition”—a rotating one. The women on Rua dos Foros would take turns baking.

My grandmother might bake eight or ten loaves of bread or massa sovada (think Portuguese challah) on a Monday. On Tuesday, a neighbor would do the same. Wednesday, another woman’s turn. If you ran out of bread or massa, you didn’t panic or run to the store; you simply went to the house of whoever was baking that day and borrowed a loaf. And when it was your baking day, you knew someone would show up at your door, empty-handed and hungry.

No one went without. The tradition wasn’t “this exact sweet bread on Christmas morning.” The tradition was “we quietly take care of each other.”

The recipes below—caldo verde, pastéis de bacalhau, bifanas, papo secos, bean soup—these weren’t reserved for high holy days in our house. They were Tuesday-night food, Sunday-afternoon food, just-because-someone-was-in-the-mood food.

But around the holidays, I became more aware of them. Aware that this was our version of tradition: my father’s wine in the sausage, my aunts’ hands in the dough, my Vo Leite’s soft voice whispering instructions over mountains of flour. Aware that every bowl of soup or custard tart carried a quiet bit of symbolism—of leaving no one out, of stretching what we had, of sharing the load.

So if you didn’t grow up with capital-T “Traditions,” here’s your permission slip:

Let the process be the ritual. The memory you’re making might be a sink full of sticky bowls and a floor dusted with flour, not the final Instagram shot of the tart. That counts.

Borrow from someone else’s oven. Make a neighbor’s soup, your partner’s grandmother’s cookies, my family’s caldo verde. Like those women on São Miguel, we’re all just borrowing loaves from one another.

Use what’s in your hands. Maybe you’re starting with store-bought chouriço instead of your father’s. Maybe your “wash tub” is a scratched-up mixing bowl. The holiness is in the stirring, not the equipment.

Repeat what feels good. If you make something this year that brings you even a flicker of comfort or connection, make it again next year. That’s how traditions begin—one ordinary December at a time.

That’s the Old-Country spirit, even if you, like me, grew up a few thousand miles—and at least half a generation—away.

The Recipes

Pasteis De Nata (Portuguese Custard Tarts)

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 4.83 from 316 votes

This pastéis de nata recipe makes as-close-to-authentic Portuguese custard tarts with a rich egg custard nestled in shatteringly crisp pastry. Tastes like home, even if you’re not from Portugal.

Caldo Verde

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 4.85 from 119 votes

Portuguese kale soup, caldo verde, is something you’ll experience literally everywhere in Portugal, from Lisbon’s trendiest restaurants to farmhouses scattered at the edge of villages. Understandably so. Its simple yet sustaining character is appreciated everywhere.

Pastéis De Bacalhau (Salt Cod Fritters)

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 4.94 from 47 votes

These Portuguese salt cod fritters, called pastéis de bacalhau, are made with salt cod, potato, onion, and parsley and are fried for a traditional Portuguese treat.

Bifanas (Portuguese Pork Sandwiches)

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 4.86 from 48 votes

Bifanas are traditional Portuguese sandwiches made with thin slices of pork that are marinated and simmered in a sauce of white wine, garlic, and paprika and served on soft rolls with plenty of mustard and piri-piri sauce.

Papo Secos (Portuguese Rolls)

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 4.84 from 62 votes

These papo secos are light and airy Portuguese rolls that are the perfect vehicle for the classic --marinated pork slices--or your favorite sandwich fillings or simply a smear of butter.

Portuguese Orange Olive Oil Cake

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 4.91 from 150 votes

This Portuguese orange olive oil cake has an unforgettably tender crumb and a citrus smack thanks to fruity olive oil, winter navel oranges, and orange zest.

Carne Assada em Vinha d’Alhos

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 4.8 from 33 votes

This Portuguese carne assada from my VERY Portuguese Mama is a traditional Azorean braised beef dish made with meltingly tender meat, small red potatoes, chouriço, and onions in wine and garlic. It’s what Indian vindaloo is based on.

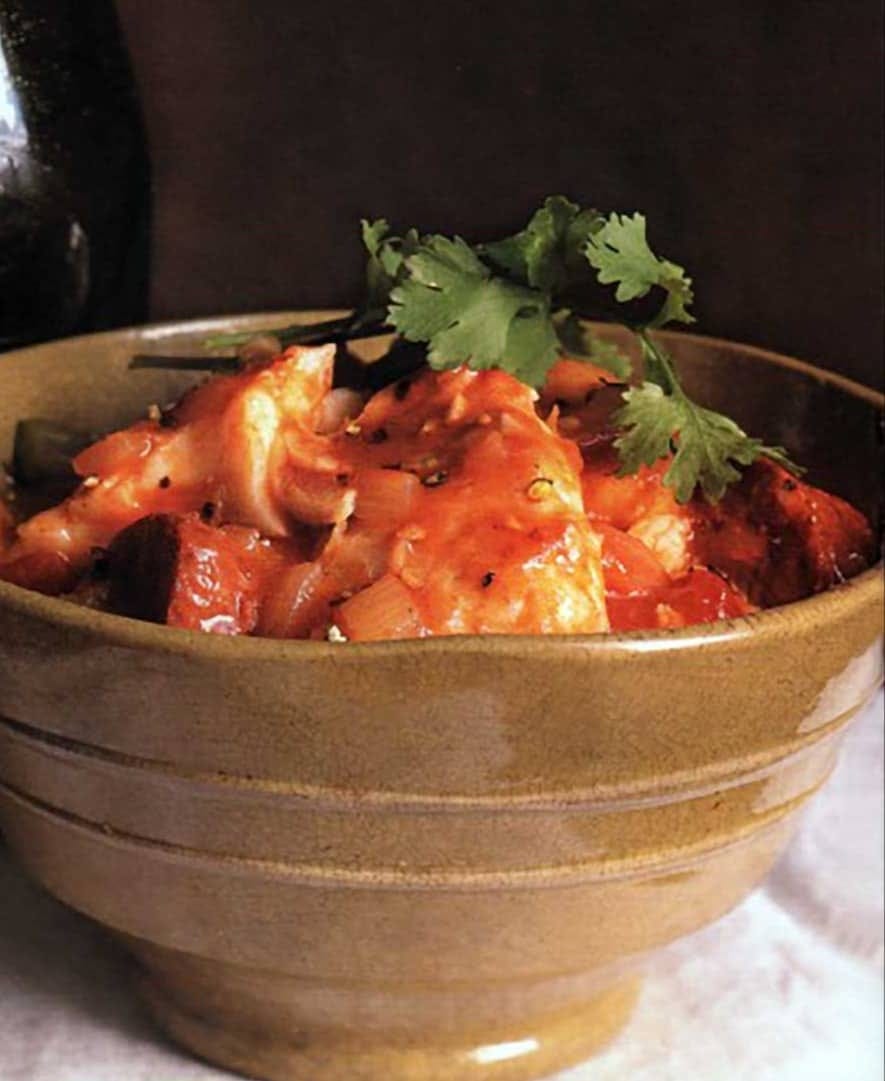

Portuguese Fish Chowder

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 5 from 6 votes

This Portuguese fish chowder is a tomato-based combo of stew and soup and chowder made of fish, potatoes, chorizo, also known as chouriço, and peppers that’s a time-honored classic in Portugal.

Portuguese Sausage Frittata

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 5 from 6 votes

This Portuguese sausage frittata calls for eggs, chorizo or chouriço (Portuguese pork sausage with garlic), onions, and potatoes. Serve it for breakfast, late supper, or cold as a snack.

Portuguese Bean Soup

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 4.89 from 17 votes

Perfect for a leisurely afternoon cook, this is one of those soups where you throw everything in the pot and simmer until pau (finished). Usually, the strong seasoning of homemade sausage is enough to flavor the broth, but if you’re using a milder store-bought variety like I often do, you can supplement the warm flavor with a little pumpkin pie spice.

Chow,

P.S. Won’t you consider tapping the ♥️, restacking this post, and/or leaving a comment? It takes but a moment, but its impact is enormous! xx

Thank you for the inspiration and love of "tradition". Living in a city with strong ties to Portugal, I will go the Neighborhood Restaurant for my soup, cod cakes, and pastel de nata. The stews are definitely on my list to cook in the coming month. I will pick up some chouriço at the Market Basket. Their chouriço comes from Fall River.

David, you’re an incredible writer. This essay is especially poignant and I must say, your writing is as rich and filling as any dish I’ve made of yours over the years.