The Garden of Him

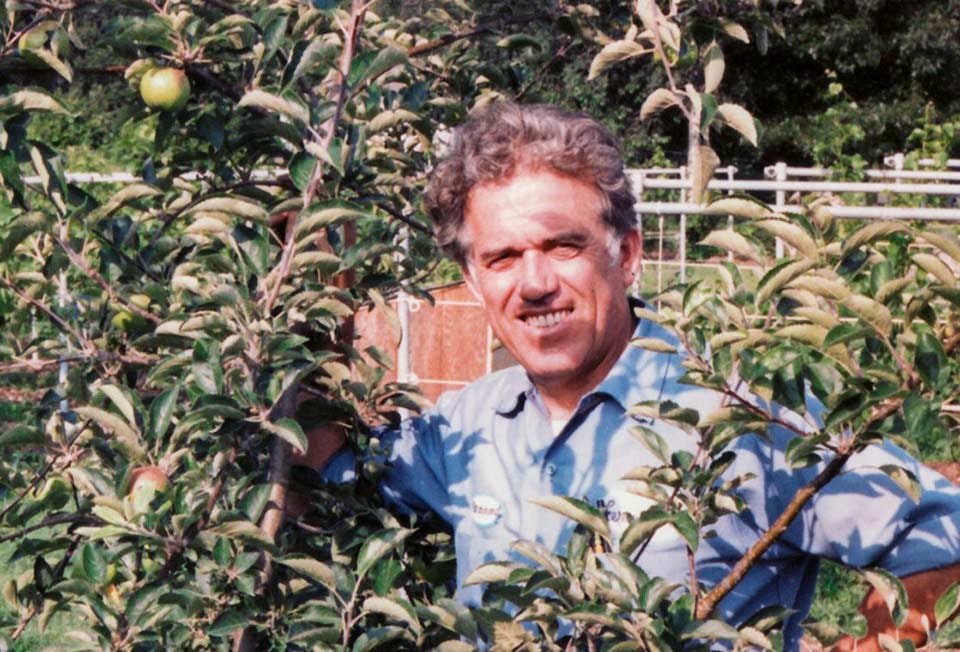

My father raised many things, including a son who took a lifetime to appreciate his dad's gift.

This is the fifth Father’s Day without my dad, Manuel Leite, who died after a long, brutal battle with mesothelioma and congestive heart failure.

We had a complicated relationship. When I was growing up, we didn’t “get” each other. Being an Azorean immigrant, he was preternaturally connected to the earth; I hated manual labor. I loved everything to do with pop culture; he just shook his head and shrugged.

During the last several years of his life, we grew very close. Old resentments, arguments, and misunderstandings just didn’t seem worth clutching.

Then, in December 2019, after a three-hour drive, I burst into the breezeway of their home to surprise my father. He and my mother were shrugging on their coats and heading to the garage. My mother shook her head. Translation: Don’t make a scene.

As I was helping my dad into the car to take him to the hospital for the thirteenth and final time, he looked at me with pained eyes and said, “Son, I want to die.” Biting back tears because my mother was in the backseat and would throw a fit if anyone cracked, I kissed him on the cheek and whispered, “I know, Daddy.” And then…“I’ll do all I can to help you.”

After three agonizing weeks in the cardiac ICU, he called me close, pulled the intubation tube to one side so he could speak, and said, “I’m done.” He asked me to have the nurses take him off morphine and stop the pump that was draining his lungs.

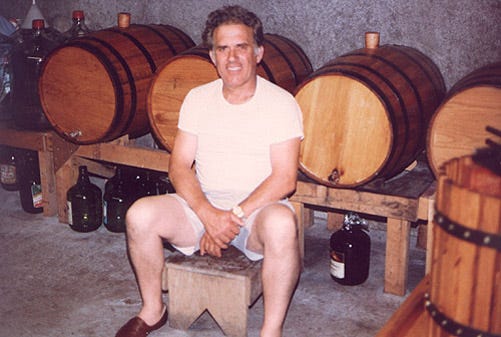

Once the morphine wore off and he was free of medical interference, he rallied; apparently, that’s common before death. I don’t mean mustering the strength to squeeze a few hands and smiling beatifically. I mean rally. Deprived of food for three weeks, he ate and drank with gusto. He asked me to bring him some of his homemade wine. He flirted shamelessly with the young nurse in front of my mom and had me dial his sisters in Boston, and in a big jovial voice grated raw by the tubes, invited the extended family to visit the next morning.

On a roll, he motioned for a piece of paper. In his nearly unrecognizable handwriting, he scribbled, “My dearest son, I will always love you and momma. Love, Daddy.” I didn’t care what my mother thought. I let myself fall apart. My dad summoned me up to the bed, and we held each other, crying, snot running down our faces. Tears gave way to laughter as we realized the lunacy of it all. Then, quiet, looking at each other, understanding the panicked urgency of the moment, we cried again—uncontrollable, deep-belly, cleansing sobs.

A while later, my parents’ pastor and his wife stopped by, and the party atmosphere returned. With my father holding court from the bed, I slipped out, certain he had another day or two in him. Back at my parents’ home, I was getting ready for what I was sure would be my first restful night in weeks.

Several minutes later, my mother called. “Please pick me up.” It was her time to weep.

To honor the man who taught me so much, I'm posting my 2015 Father’s Day essay about Papa Leite.

MY FATHER is a good man. Just ask my mother. Actually, if you spend enough time with her, she’ll tell you anyway, blurting it out while watching TV or holding out a bag of mini Milky Way bars to you. “Manny Leite's a good man,” she'll say.

The measure of a good man is calculated by many yardsticks. For my father, it was being a provider. It began with a home. First, was a floor, covered in the lightest of oak—“Only three-quarter-inch will do,” he’d say—that supported us. Then, two-by-fours that became walls that surrounded us. Finally, a roof that protected us, all built with his own hands.

Then there was sustenance. He cut a swath from what has to be God’s rockiest half-acre, situated behind our house. A grape arbor appeared first. Beneath it, we lingered over many long, lazy meals, just we three. Plump bunches of grapes hung heavily, and my father would pluck some and feed them to my mother. The shaded table grew crowded with our expanding family my father brought over from the Azores. First my grandfather, then my uncle, my aunt, another aunt, and finally my grandmother and the youngest aunt of all. And, in time, their spouses and, later, their kids gathered round. It was understood back then that this half-acre was on loan: It was meant for me, my wife, and my children—a family that would never come to be.

A small vegetable garden replaced the arbor, way back in the '60s when my father’s shovel was taller than me. A few parallel lines of plants I can barely remember. But as my father came to understand that I would never live there, that my future lay somewhere else—somewhere I wasn’t so asthmatic, wheezing at the confines of a small New England town—the plot grew, and he weeded more rocks from it. Enough rocks to make a wall around the side of the property. He planted tomatoes, onions bigger than softballs, waxy long red peppers, big bouquets of satiny-looking kale, corn with its incessant hissing of leaves in the wind, and potatoes. Always potatoes. My father loves potatoes. I love my father’s potatoes.

We had little in common, my father and me. Oh, we were similar in some ways. We didn’t like sports, and neither of us ever delved much into books. And, of course, we shared values and morals. How could we not? They were his and my mother’s, and they taught me well.

But left alone, he and I didn’t have much to say to each other. How many times did my mother elbow me: “Go outside and help your father.” I’d pull back the lacy curtain to see him, the rototiller bronco-bucking in his hands, tearing up the earth for another year’s worth of vegetables. Or snapping suckers off tomatoes. Or tying up the grapevines that had come to take up half of the half-acre.

I wanted nothing to do with that work. It was manual labor. It was also Manuel’s Labor. I was convinced it wasn’t work meant for me. “I’m going to hire someone to do this when I get older,” I would tell my father, after I was forced by my mother to help lift rocks into the barrow and wheel them, weaving as if I were plastered, to the growing stone wall. He’d wince and shake his head. I thought he was being judgmental, even smug, but my father isn’t a smug person. I see now he was wounded that I didn’t find value in what he held so sacred.

Gardening wasn’t a luxury for my father when he was growing up. It was survival. Back in the Old Country, if you didn’t garden, you didn’t eat. Small squares of land, no bigger than our front cement porch, would have to supply a family of seven. I think he always held the fear of going hungry again.

I don’t know what it was that seized me this year to want to create a big garden. I’m a lousy gardener. But there I was, overseeing the construction of four huge raised beds. Annoying J.D., the carpenter, with my constant comments, my million little adjustments. Aggravating Ron, the yard guy, with questions about exactly how organic his organic soil was. Bullying The One into planting the rows the way I wanted them—the way I remembered my father planting his.

What I’ve never told The One in 23 years is that I understand plants far better than I’ve let on. For two or three summers, beginning when I was 13, my parents sent me to work on a farm as a way of, hopefully, combating what we later learned was terrible depression. I’d never copped to my horticultural understanding so I could avoid work. But there I was in our backyard, standing in front of three beds The One and I had planted, a fourth waiting to be seeded, and I felt something. I felt something of my father in me.

It was the potatoes, my father’s potatoes that he gave me to plant, that did it. I had fantasized they were potatoes that had been in our family for 25, maybe 30 years. But their lineage goes back only a few years.

I began calling him, asking how deep and how far apart I should plant them, sending photograph after photograph, asking for the precise places to cut through the tubers so I could maximize my yield. The thought that in about 75 days, I would be eating potatoes that were related to those from that half-acre of rocks back home moved me something fierce.

And it filled me with awe and guilt and closeness. I blubbered on the phone, eyes nearly swollen shut, a knot burning a hole through my throat as I spoke to my father. I felt connected to this good man. I began to appreciate the lure of the garden, to understand the pleasures he found among the plants. Unlike writing, my trade, whose harvest at the end of the day is never guaranteed, gardening always promises something. There is no such thing as gardener’s block. Nothing wishy-washy, no doubt or self-recriminations. You plant, you hoe, you feed, you weed, you harvest.

When I go out to the garden, I think of my father. It’s a contemplative time when I hoe my worries, weed my discontent. I wonder what my father used to mull over when he was alone in his garden when I was younger.

The strange sadness and fear that gripped me? My possibly being gay? My imminent departure, “as soon as I turn eighteen, just you watch,” which I never ceased to remind him of? I’ve never asked. A man should be allowed his mystery.

Each morning, bent over these beds, I marvel at how the broccoli has shot up another three inches. How two or three more shoots from my father’s potatoes have wormed their way up through the soil. How the tomatoes need, yet again, to be staked because they grew so quickly. How the cucumber tendrils and leaves must be woven through the fence as they climb, creating an eventual wall of green.

Yes, my father is a good man. Not so much because he has been a good provider. He proved that long ago. But because he holds no resentment that it took me 40 years to come around to the simple act of following in his muddy footsteps.

I frantically, obsessively want to know what he knows because his garden, which at one time crowded out the backyard, grows smaller each year. It's now a mere two rows, as long as I am tall. A few potato plants, fewer tomatoes, and even fewer peppers. I want, no, I need so much for my father’s spirit and his thrill of the garden to live on in me. I have no child or legacy. This garden is the closest he will ever get to a grandchild. Or to something that, though not spun from his DNA, descends directly from him.

Happy Father's Day, Daddy.

Chow,

Do you have special memories of your father or father figure you’d like to share? I’d love to hear them.

Enjoying your garden memories of your father. My father passed over 20 years ago but I have his sorrel plants coming up each year, seeds he brought back from Hungary.

I can still see my Madeira born step-grandfather’s garden in the backyard of the yellow house on 90th street in Oakland, CA. Corn, tomatoes, fava beans (of course!), chickens, squash…and the fruit trees! Apricot, peach, plums, pluots…and the lovely arbor with a tangle of passion fruit vines. Thanks for nudging this lovely memory out of the past, David!