40 Watts Later

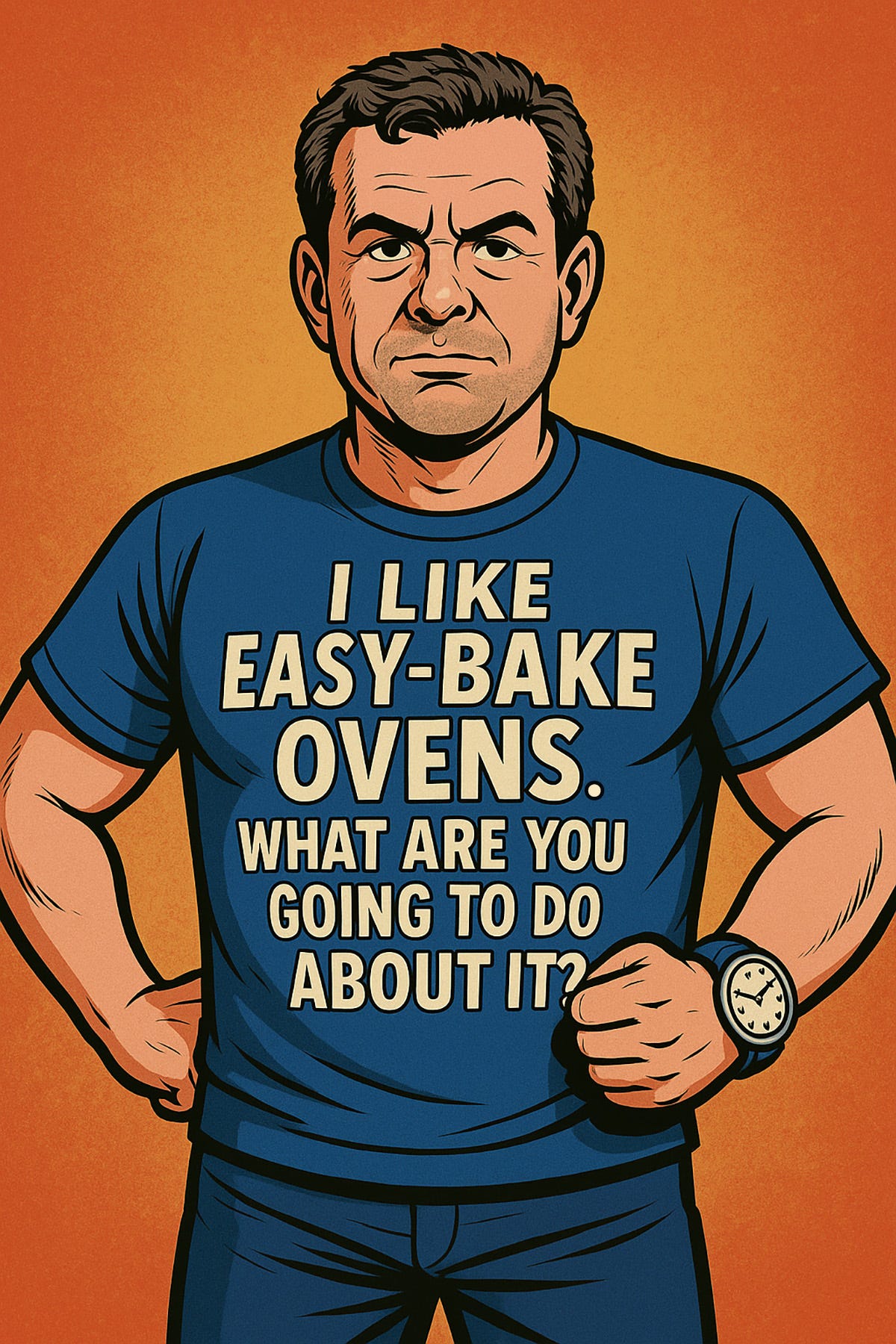

Men buy cars, boats, and watches to make up for their, um, shortcomings. A certain someone purchase stoves.

I’M BETRAYING MY GENDER by saying it, but I’ve done worse: I believe there’s some truth to the notion that emotionally small men buy big things. Big car. Big houses. Big companies. I wouldn’t be surprised if the founders of Costco and Price Chopper, emporiums of everything super-size, were men with wobbly senses of masculinity.

I find these blatant shows of manly compensation to be amusing. I roll my eyes and snicker into my sleeve whenever I watch some guy in a Cybertruck, blasting Kendrick Lamar while leering at a phalanx of leggy blondes crossing the street with that stupid “How-you-doin’” look on his face.

Invariably, I have to choke back the impulse to shout, “Yo, buddy, sorry about your dick.”

No one could ever accuse me of such obvious psychological compensations: I drive a modest car, play music at a conservative volume (except when I’m alone and Gloria Gaynor is on the radio; old disco habits die hard), and wear a watch that costs less than most DVDs. So why am I cooking on an industrial-size stove with a 15,000-BTU capacity, a burn-the-hair-off-your-forearms broiler unit, and an oven that can hold a 25-pound Christmas turkey with all the trimmings and still have room for a tableful of pie? Not to mention the stove’s vented hood, which is so powerful it can double as central vacuum cleaner.

“Ohmygod,” I said to my friend Jennie one day over lunch, “it’s a case of the cook doth protest too much. I’m no better than any of those other guys: They drive their male inadequacies; I cook on mine.”

She patted my hand and picked at her salad. “But, sweetie, you need it for your work.” I was reminded of an enormously successful food writer I know who has never used anything but a doll-size 22-inch Caloric range and has never been behind the wheel of a car.

”It’s my cousin Shirley’s fault.”

“You mean because she berated you all the time?” she asked brightly.

“No, but, jeez, thank you for reminding me.”

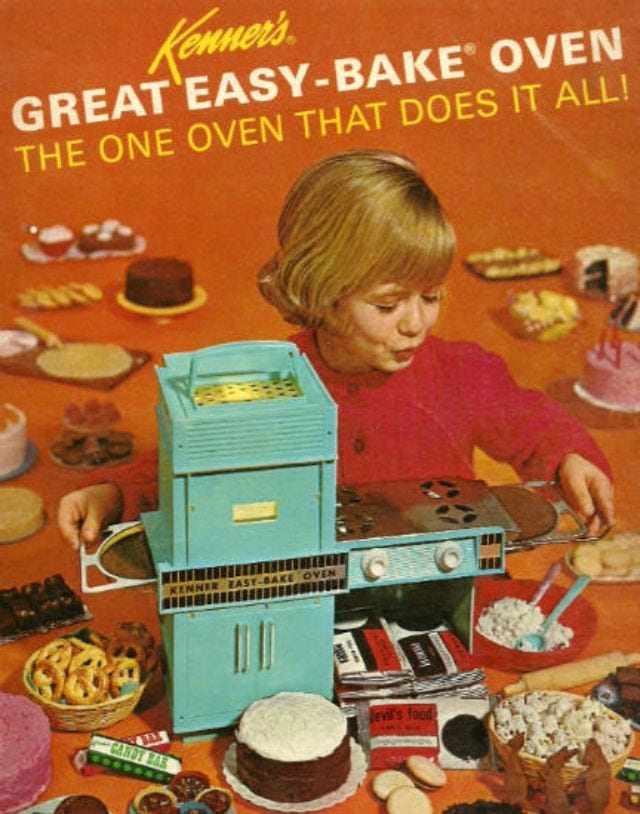

The evil that Shirley wrought was far, far worse. When I was nine years old, the entire family gathered on Christmas Day at my Uncle Tony and Aunt Vi’s house. As was customary, all of my cousins had dragged along their favorite toys, and we were shunted into the living room by the adults, who sat around the dining-room table smoking Lucky Strikes and complaining about how much our presents cost. Out from the kitchen came Shirley with a teal-green plastic box tucked under her arm, a smirk on her face.